"Taken individually, the pictures below [not pictured] are merely that - pictures. However, when part of a sequence, even a sequence of only two, the art of the image is transformed into something more..." (pg. 5)

Central to the idea of the comic is the concept of sequence. There is an order to pictures/words/images/events/etc that gives them meaning. The narrative of a particular text is meaningful because of the sequences that interact (plot, characterization, the various nuts and bolts of a story) inside of it. It's progressive - image A leads to image B leads to image C (for example), and so on and so forth. Long story short: a sequence makes a narrative.

It doesn't even have to be a linear narrative - the sequence that makes up a non-linear narrative is still a linear sequence, because time is still just one of the thing that make up a text. Star Wars is actually a great example of this: narratively, it opens in media res, but A New Hope is the first movie sequentially - even though it is fourth in the timeline.

(messing with your preconceived notions about narrative and timelines since 1977)

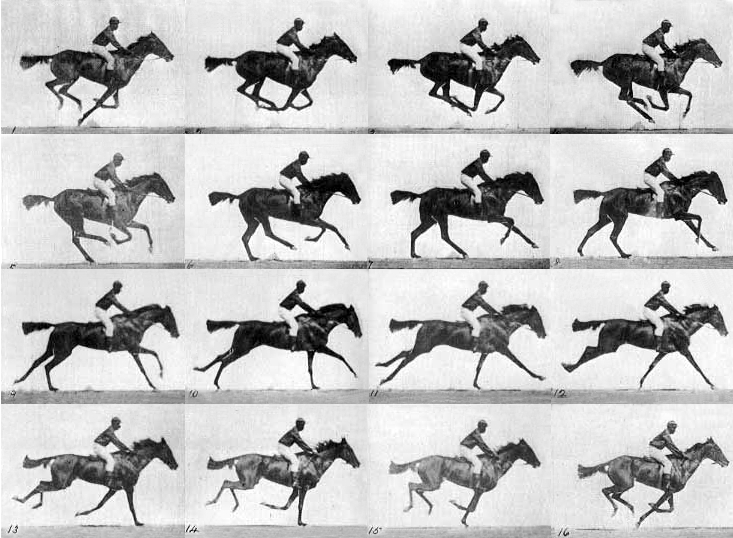

McCloud brings up the idea that "space does for comics what time does for film" (pg. 7) Comics are spatially sequenced; the space between them is the sequence. Comic action happens in the blank lines between each frame. To help myself visualize this, I remembered my junior year of high school, when I had to learn about early photography in either Photo 2 or AP Art History. Here are the frames of Eadweard Muybridge's work with horse racing:

Eadweard Muybridge, Human and Animal Locomotion series, 1887

Now here's the same thing, only animated:

(same citation, but accessed on Wikipedia)

There's still a gap from point A to point B. If you look at the sheet (if you want to call it a storyboard, I guess you could - I'm pretty sure there's a term for all those frames lined up, but I can't remember what it is) you see that there's missing action - we don't see the horse's leg go from straight to bent. That's action we missed, that we didn't see. The meaning is not only in points A and B, but how we get there, the space that makes them different.

(A random aside: I was thinking about how so many comics are adapted to film, and I began to wonder if filmmakers in general don't like to read comics because comics are so reminiscent of storyboards - maybe almost like comics are unfinished, unrefined bits of a larger work? Or maybe they like to read them for much the same reason? I'm not sure. Who knows?)

Sources:

McCloud, Scott. Understanding Comics:. New York: Harper Perennial. 1994.18. Print.

JJ, I like your example of the Human and Animal Locomotion series. I believe this will classify as a "moment-to-moment" transition or a "action-to-action" transition? There is some gaps that we miss, but I argue that this type of transition is boring. We all know what is happening and we do not do much mental work. I like to guess how the images fit together and how the plot will develop, rather than to look at frame by frame and sort of experience it in slow motion. "Scene-to-scene", "aspect-to-aspect", and "subject-to-subject" are more stimulating. What if we took that storyboard (don't know what to call it either) and in between we zoomed in to the person, then we cut the finish line, then we cut to the horse, then to the entire picture, then to the person, and finally we cut the them crossing the finish line. That is more exciting and intriguing. I guess you can say that the space in between the frames I made up would have more meaning to me.

ReplyDeleteIt is interesting how our minds automatically assume what we don't know. Even though some time has elapsed between the images in the horse racing sequence, virtually everyone will interpret it as snapshots of fluid motion. However, I imagine that as more time elapses between images, or their connection to one another becomes less distinct, then interpretations of image sets begin to vary. McCloud's best example of this is on page 66 - in one panel, a man appears to be chased down by someone with an axe. In the next panel, there's a night scene of a city and someone seems to have screamed ("Eeyaa!") Nevertheless, whether or not the man was killed is left to one's own interpretation.

ReplyDeleteJJ,

ReplyDeleteYour in depth analysis of the sequence in which comics are displayed is perfect! How the comic writer is able to place a certain phrase, picture, or frame can influence the timeline of the story immensely. With this being said, I find it to be incredibly interesting how these small details are so powerful. The Human and Animal Locomotion series describes this best.

Interesting point about filmmakers and comics: while I can't speak for certain about filmmakers in general, I know that some well-known ones have pointed towards comics as sources of inspiration for them. Christopher Nolan has spoken glowingly of Batman: The Long Halloween (which I actually have with me), described it as a masterpiece, and based many elements of The Dark Knight off of its storyline. Zack Snyder's also a major comic book fan, and it shows in his style of filmmaking. When he worked on the adaption of Watchmen, he used panels from the comics as storyboards for the film, instead of creating new storyboards altogether. I would imagine that they get better appreciation from filmmakers than books, because of how much easier it is to recreate moments from them in movies.

ReplyDelete