Two comics immediately came to mind when I finished that page - Will Eisner's The Plot, and Art Spiegelman's Maus. I read both comics in high school, during a time when I voraciously read through much of Archbishop Spalding's fiction library. Though I had to read Maus for my sophomore English class, I read The Plot on my own time. Nevertheless, I was captivated by the combination of art and prose in both comics.

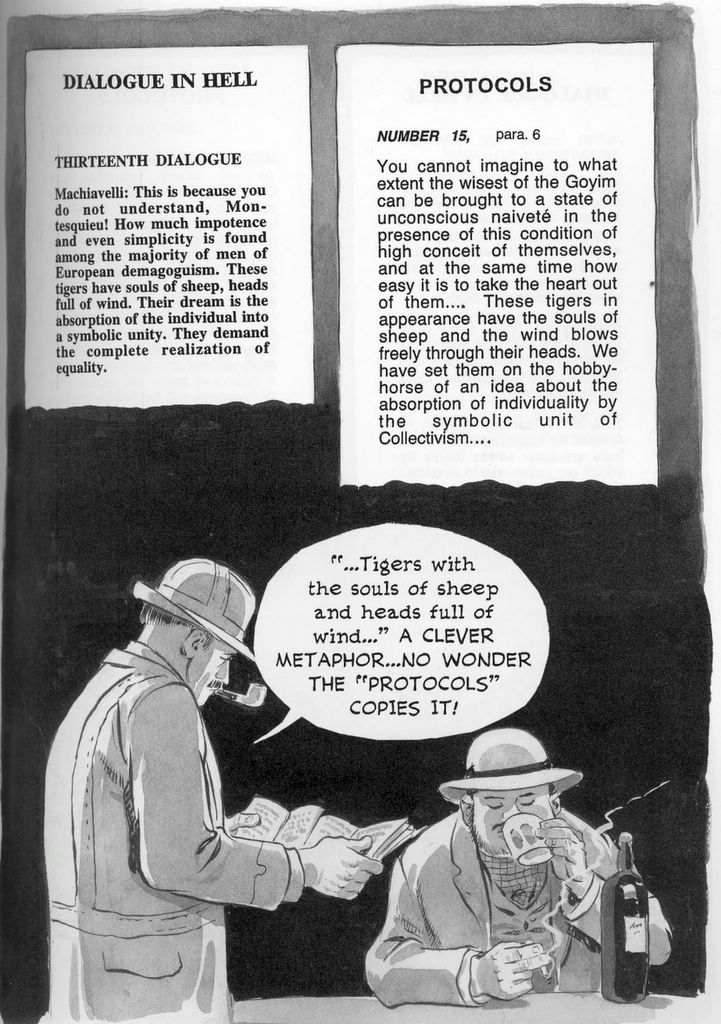

The Plot, a detailed account of the fabrication of the Protocols of the Elders of Zion, had a unique art style that combined detailed character designs with exaggerated expressions. It told a story that spanned centuries and involved disgruntled French authors and conniving Tsarist advisers desperate to hold onto power. It was a well-researched and tragic tale that kept my interest throughout its length. Why, then, is it never brought up in any way, shape, or form when high-quality non-fiction is discussed? Is it the "cartoonish" artwork that prevents critics from taking its contents seriously, no matter how thought-provoking it may be? Or did its black sheep status as a non-fiction comic keep it in obscurity?

Of course, it is entirely possible to break free from the "ghetto" that most comics reside in, and establish a comic as serious reading material. Maus fits this idea to the T.

I remember my surprise at Maus being taught like the other books in my curriculum. While its subject matter was serious, it looked like any other comic sidelined for not fitting the standards of a "serious book." I enjoyed both volumes of Maus, as tragic as its depiction of the Holocaust was, but a question irked me throughout my reading of it: why this, and not The Plot? Both dealt with anti-antisemitism, historical events, and the depths of human depravity when dealing with "outcast" groups. Didn't both deserve credit for taking serious risks and presenting their material in an unorthodox, easier-to-consume format?

I do not think there is an easy answer to those questions. Sometimes, it might boil down to sheer, dumb luck. Critics in all fields are known for their bizarre tastes - the much-hated and generally-unfunny Ghostbusters reboot currently holds a higher Rotten Tomatoes rating than the moody, thought-provoking "Only God Forgives" and a near-equal rating with the uncompromising "Falling Down." Some practical elements may have factored into this discrepancy: Maus was published nearly three decades ago and had a stagnated release, while The Plot is only 11 years old.

"What are you driving at, exactly?" You might ask. Well, it all comes down to this - like what McCloud said, anyone defending comics has the deck heavily stacked against them. Though the old-fashioned view of comics being for nerds and children no longer holds water today, it lingers in the backs of society's attitudes. We scoff at comics as being below us, yet we cannot put our fingers on why most people hold that view.

Granted, for every Batman: The Long Halloween and Watchmen, there are dozens of disposable comics churned out by Marvel, DC, and other companies. But we should never allow our view of a medium to be tainted by its worst examples. Should all of literature be tossed aside because of Twilight and 50 Shades of Grey? Of course not, so why should comics be viewed as an inferior medium due to the existence of garbage like Nightcat?

Comics are undeserving of the second-class status society has lumped upon them. They deserve to be treated like any other piece of literature, not as a minor amusement.

Sources:

Eisner, Will, and Umberto Eco. The Plot: The Secret

Story of the Protocols of the Elders of Zion. New York: W.W. Norton, 2005.

Print.

McCloud, Scott. Understanding Comics:. New York:

HarperPerennial, 1994. 18. Print.

Spiegelman, Art. Maus: A Survivor's Tale. Vol. 2. New York: Pantheon, 1986. Print.

I agree with your assessment of comics as a whole. There certainly are examples of throwaway-comics, just as some comics are artistic masterpieces.

ReplyDeleteThat being said, I wonder how the public perception of comics will change in the coming future. I think it's fair to say that most of us who grew up with comics are adults now - some of us being older than others - and we are having an impact on our society in multiple ways as far as comics are concerned. For example, famous comics are being turned into movies, which is exposing aspects of comic-culture to large audiences world-wide. I think this impact we're having - this exposure of comics to the non-believers - is changing, and is going to continue change the public perception of comics for the better. After all, we are studying comics in an upper-level college course, so I think it's safe to say that we're making some progress.